Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony

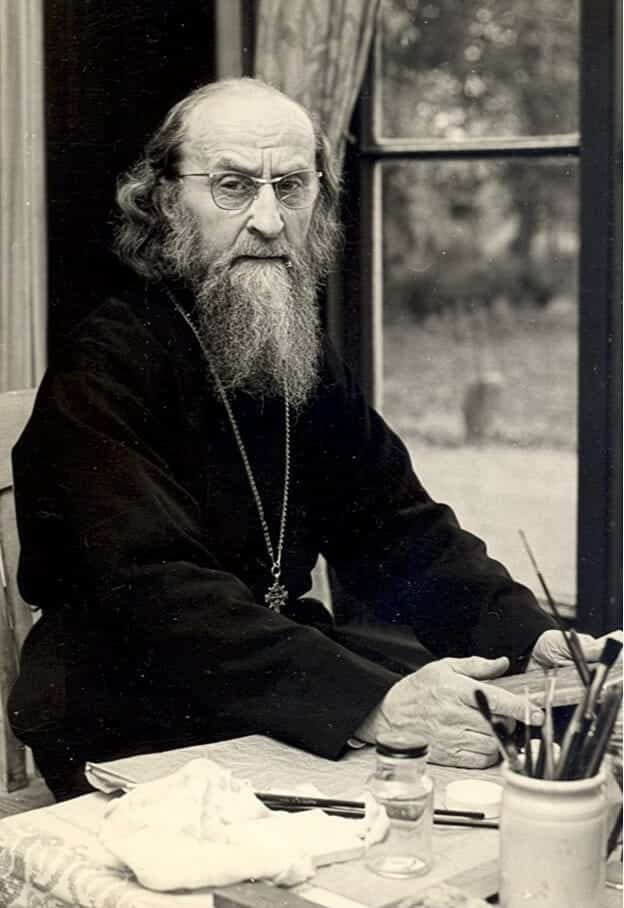

It is with a sense of deep gratitude, joy and honour that I embark upon the task of summarising a series of three exceptional monographs on the subject of the artistic path and iconographic legacy of Saint Sophrony the Athonite (1896-1993).1Hereafter to be called Father Sophrony, reflecting Sister Gabriela’s preference throughout her books. At the initial publication of this article in January 2019 St Sophrony was not yet canonised. The works in question are: Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony (2014), ‘Being’: The Art and Life of Father Sophrony (2016), and Painting as Prayer: The Art of A. Sophrony Sakharov (2017)2All published by the Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex. by Sister Gabriela, a member of Father Sophrony’s monastic community of Saint John the Baptist in rural Essex, England.

Sister Gabriela who, most significantly, is an iconographer and artist herself, was eminently suited to this task having lived and worked closely for many years with Father Sophrony, who was also her spiritual father and artistic director. She had the benefit of being able to draw on his extensive writings, her own detailed personal notes and recollections, as well as those of the community as a whole. In addition to this, much painstaking research was undertaken in the creation of the books, resulting in the unearthing of a treasury of new discoveries which will fascinate and edify all those who have an interest in iconography, theology, art history, artistic theory and practice, and of course the life and work of Father Sophrony.

Written with great intensity over a period of three years, these unique publications are ground-breaking in their content, breadth of field, method of approach, and their deep reflections on the artistic practice and spiritual development of a holy Elder of our times whose contribution is only beginning to be fully appreciated. This mirrors the uniqueness of Father Sophrony’s own exceptional path; his was truly a life hors concours, and one that offers to us many a precious ‘word’ and example for our times.3Cf. 1 Corinthians 4:15-16. Until now, the writings and life of Father Sophrony have become well known, whereas his artistic contribution and journey have remained largely unexplored. The books of the trilogy aim to rectify this.

It must be added that there is also a sense of trepidation as it is not possible to discuss the artistic path of Father Sophrony without also including some of his theological perceptions, which are inextricably bound with his artistic path and work, and gained through many decades of monastic asceticism as a spiritual father and hermit in the ‘desert’ of the Holy Mountain, a disciple of the revered Saint Silouan the Athonite, and finally as an Abbot and Elder for the last thirty years of his life at his own monastery in Essex. These profoundly inspired theological insights extend far beyond my poor commentary and I ask forgiveness in advance for this.

Thus we shall begin our exploration of his extraordinary life as elucidated in the first of the trilogy, ‘Seeking Perfection in the World of Art: The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony’. Sister Gabriela begins by taking us on a journey back to the late 1800’s, to Holy Russia before the Revolution and the early formative years of Father Sophrony who at that time was known as Sergei Simeonovich Sakharov. The young Sergei was born in 1896 into a highly cultured family in Moscow two years after the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II. From the youngest age he spent many hours in church with his nanny and ‘would ponder on eternity…reflecting more and more on the infinite, on that which goes on forever.’4‘Seeking Perfection’, op. cit., p.22, and Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), ‘We Shall See Him As He Is’, Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 1988, p.10. He also showed pronounced artistic gifts and would draw all day even before he learned to speak.

He only knew peace in his earliest childhood (up until the age of eight), after which Russia was rent asunder by war and conflict, initially the Russo-Japanese war, then the first revolution in 1905 and the First World War in 1914, followed by the tumultuous October Revolution and the Civil War (1917-1922). This had a profound and permanent effect on the young Sergei who later wrote, ‘…my life span has coincided with all the terrible events of our century…With the outbreak of the First World War the problem of eternity began to predominate in my mind. The news of thousands of innocent victims being killed at the front placed me squarely before a vision of tragic reality. It was impossible to come to terms with the fact of vast numbers of young lives being brought to a senseless, cruel end…I had only begun to perceive myself as a human being: my heart was aglow with good intentions, seeking perfection like all young people, aspiring to the light of universal knowledge.’5Ibid., p.23, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., pp.10-11.

During most of the October Revolution in 1917 Sergei was ill with typhus and was uninvolved. He was however, deeply affected by the tragic events which ‘became engraved, as it were, on my soul’.6Ibid., p.25. His urgent search to resolve the ‘question of eternity’ at this point took him away from Christianity and into eastern mysticism, a departure that ‘he later regretted for the rest of his life.’7Ibid., p.25.

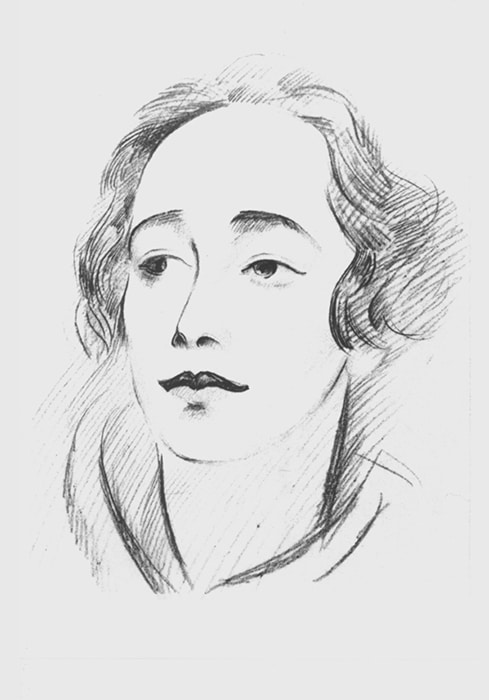

Sister Gabriela brilliantly depicts his life and spiritual state at this time, and goes on to describe his artistic training in Moscow, beginning with his studies at the school of the painter Illya Mashkov (1881-1944) and thence to the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in 1918, which after one year was reformed under the new government into the SVOMAS (the Free State Art Workshops/Studios), and later transformed again into the Vkhutemas (the Higher State Artistic-Technical Workshops). Sister Gabriela contextualises Father Sophrony’s background, giving us a tour in brief of the history of Russian art, the development of its artistic academies, its leading patrons and collectors, the ‘rediscovery’ of the icon in the early 1900’s and its subsequent adoption by the avant-garde, the leading painters (such as Petr Konchalovsky (1876-1956), Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and the artistic groups and movements of the time. Sergei’s teachers Konchalovsky, Mashkov and Kandinsky are described and the methods by which he was taught. From this period there survives a fine and expressive drawing made by Sergei of Eugenia Lourié (1899-1965) made during his time in the workshop of Konchalovsky.

The influence of one of his teachers, Wassily Kandinsky, is also explored, which Sister Gabriela says was ultimately more impactful on his work in the written rather than the painted form. Father Sophrony later said of Kandinsky, ‘In my young days, through a Russian painter who afterwards became famous, I had been attracted to the idea of pure creativity, taking the form of pure painting.’8Ibid., p.58. Kandinsky taught that ‘students should have an inner life, in order to be able to work artistically, to create, feel and understand the creative process. Painting should come from within, the soul.’9Ibid., p.60. The author writes that ‘…most artists of the time searched to further their inspiration on the spiritual plane. In their search, they often turned to sophism, oriental religions and even spiritualism…Both Sergei Sakharov and Kandinsky moved in circles where it was common to explore such beliefs and practices. The idea of “pure creativity” fitted well with the eastern idea of losing oneself in nonexistence.’10Ibid., p.63, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., pp.8-9.

Although initially Sergei was engrossed by abstract art, in 1921 he realised,

‘…it was not given to me, a human being, to create from ‘nothing’, in the way only God can create.’11Ibid., p.64, and Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), ‘Wisdom from Mount Athos’, Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, 1974, pp.13-14.

With this thought, Sister Gabriela writes that ‘…he turned again to the God of his childhood, Whom he had abandoned in his youth in search of what he had then thought were loftier things.’12Ibid., p.64. At this point he also returned to figurative painting, working with great intensity until his departure to Europe.

After leaving Russia, he travelled throughout Italy and some of his reflections on Italian liturgical art already demonstrate a developed eye for liturgical subject matter and a keen interest in it, although his own work was, at that time, far from this. From Italy he travelled to Berlin, which had become a centre of Russian emigration, but in late 1922 departed to live in Paris, which was by then the global artistic capital, was thriving and ‘an arena of endless possibilities’.13Ibid. p.82. Sister Gabriela colourfully describes for us the Russian émigré population of Paris (already become a significant colony by the early 1920’s) and its artistic community.

Sergei’s painting at this time is described as being part of the ‘Cézanèsque’ movement14A term deriving from the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). Artists whose work continued his aesthetic, methods and ideas were said to participate in the Cézanèsque movement. and was figurative in nature, focussing on landscapes, still lifes and portraiture. He worked fervently there, achieving some success and exhibiting in the primary artistic salons of the time, the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Tuilleries. In 1923 the renowned art critic Thiebault-Sisson wrote of his work exhibited that year: ‘Sakharof has two small paintings where the care of resemblance does not exclude a softness and delicacy worthy of Ricard.’15Ibid., p.93.

Nevertheless, concurrently his ardent spiritual search continued unabated. Desiring quietness and the possibility to reflect, he moved out of Paris to the suburb of Clamart, which was peaceful and rural. ‘These were times of great inner turmoil for him; inside him the battle between painting and prayer was being waged.’16Ibid., p.90. However, ‘All this travail was in vain: the disparity was too obvious, and in the end prayer won.’17Ibid. p.91, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., p.15. Seeking to further his knowledge of the Orthodox Church and to quench his thirst for prayer, he enrolled in the recently opened Orthodox Theological Institute of Saint Serge in April 1925. However, by Autumn his desire for prayer had become so intense that he abandoned his studies, his painting and life in Paris, departing for a life of monasticism on the Holy Mountain of Athos. He entered the Holy Monastery of Saint Panteleimon and ‘all the creative energy that he had earlier given to his art was now concentrated in prayer.’18Ibid., p.102. Here he received the name Sophrony, in 1930 he was ordained into the diaconate, in 1941 became a priest (hieromonk), and later a father confessor to monks from several monasteries, as well as hermits. During these years at the monastery it is believed that he did not paint except for two icons with which he was unsatisfied.19Ibid., p.108. Sister Gabriela indicates the existence of not only two but several icons attributed to the hand of Father Sophrony on Mount Athos. However, this question has been left aside in the book as research is still at an early stage. However, the defining event for him came in 1931 when he met the profoundly humble and self-effacing Russian monk Staretz Silouan (now Saint Silouan the Athonite), who became his spiritual guide and at the end of his life, in 1938, also confided his writings to Father Sophrony.

Following the repose of his staretz Father Sophrony retired to the Athonite ‘desert’ to live in seclusion, in prayer for the whole world, ‘especially during the horrors of the Second World War, which deeply afflicted his spirit.’20Ibid., p.106. As he had more time, and with the help of artistic materials from Mother Theodosia who he had known in Paris, he also now resumed the study of iconography, thereby being one of the first to renew iconography in its traditional form on Mount Athos.

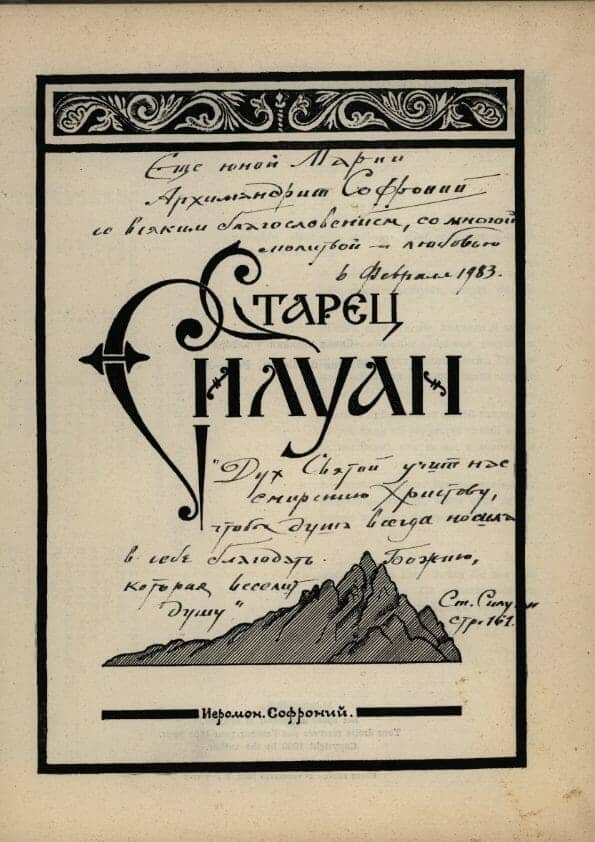

In 1947 he returned to Paris in order to compile a book containing the writings of his beloved Elder Staretz Silouan,21This book ‘Staretz Silouan’ is now entitled ‘Saint Silouan the Athonite’ (Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 1991) and has been translated into twenty-five languages.editing his writings and publishing them in roneo-type which he himself made. After this publication, he made a second edition with a lengthy introduction to the writings of the Staretz, and as well as writing this he also embellished the frontispiece, initial letter blocks and created other decorative elements for the book. However, as the process was lengthier than expected and working conditions so poor, ‘…my whole organism was so strained that I became ill. Afterwards I was operated on, and because I was left an invalid, I could not return to my desert.’22‘Seeking Perfection’, op. cit., p.107. It was predicted that Father Sophrony would not long survive.

Father Sophrony’s inscription, written in his own hand, reads:

To still young Maria

Archimandrite Sophrony

With every blessing, with many prayers and love

6th February 1983.

“The Holy Spirit instructs us in the humility of Christ, that the soul may ever carry within her the Divine grace which gladdens the soul.”

Saint Silouan p.161

He had settled in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, 23 km south of Paris, and a small group seeking spiritual guidance and prayer had gathered near him. They were offered the use of some stables with additional rooms above and one of these rooms was converted into a chapel. Father Sophrony embarked upon creating the chapel which ‘was remembered by all with especial love and nostalgia…everyone who visited it said it was the most wonderful chapel they had ever been in.’23Ibid., p.112. Sister Gabriela compellingly describes its decorative features and Father Sophrony’s great attentiveness to creating each detail and its special atmosphere of prayer. ‘Father Sophrony had created a special colour interior: the floor was red, the walls brown and the ceiling blue. This was to represent standing in hell (red), surrounded by the earth (brown) and aspiring to heaven (blue). The icons on the iconostasis were painted by Father Gregory Krug. Father Sophrony had asked him to use a palette of earthen colours, which gave the icons a particular humble look, differing somewhat from Krug’s usual scale of colours.’24Ibid., pp.112-13. Later these icons were transferred to England, to the chapel of Saint John the Baptist at the newly founded monastery.

Various now renowned iconographers active in and around Paris at that time were known to Father Sophrony, including Leonid Ouspensky, Natalia Goncharova and D. Stelletsky. However, ‘It was to Ouspensky that Father Sophrony confided the task of painting the first icons of St Silouan, then still called Staretz Silouan. Ouspensky painted about five icons, creating the iconographic portrait of the Staretz.’25Ibid., p.115. He also selected the text for his scroll ‘I pray Thee, O merciful Lord, for all the peoples of the earth, that they may come to know Thee by Thy Holy Spirit.’26Ibid., p.115, and ‘Saint Silouan’, op. cit., p.274. It was also to Ouspensky that Father Sophrony would send his monks to learn the practice of iconography, both while in France and subsequently from his monastic community in England.

After his operation Father Sophrony was left extremely weakened for several years and was consequently moved to a local convalescent home. However, characteristically, he continued to write, to teach and to minister to the needs of those all around him. Many people came to visit him and he dedicated all his strength to them and his small community. After several years an opportunity arose to found a new monastery for the community, which according to God’s wondrous providence was in Essex, England, and Father Sophrony and they departed thence in 1959.

Sister Gabriela next turns to the topic of Father Sophrony’s creation of his monastery on Rectory Road on the edge of the village of Tolleshunt Knights in Essex. Now 62 years of age, the holy Elder and his small community settled in the Old Rectory, a Georgian building which had formerly served as a rectory to a later abandoned parish. At this point Father Sophrony was necessitated to turn his attention to the design and building of the new monastery, an activity which he took extremely seriously, never overlooking any subtlety or nuance. The author writes that ‘One can trace Father Sophrony’s artistic and aesthetical sensitivity running like a thread through the construction and development of the monastery.’27Ibid., p.121. The most pressing task was to create a chapel, which would be dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. The same icons by Father Gregory were installed which had been brought from the chapel in France and much consideration was given to the colours, materials and lighting in order to create an ideal environment and atmosphere for hesychastic prayer.28The Jesus Prayer or prayer of the heart.

It was at this moment that Father Sophrony resumed painting, dedicating himself fully to the practice of iconography. However, ‘This time round, the struggle was no longer between an artist and the inescapable limits of mortal being. It was waged by a man who, through traditional Orthodox iconography, was now expressing and transmitting the spiritual life he himself had experienced and known intimately. The artist in him joined forces with the spiritual man who had contemplated the beauty of the Lord and all His works, and everything that reflects His likeness.’29Ibid., from the foreword by Jean-Claude Polet, p.12. Sister Gabriela writes that ‘After the long period of deepening prayer and ascetical life…, this was a time of great maturity. An ascetic with full knowledge of the inner life, expressing himself in painting, is very rare phenomenon.’30Ibid., p.123.

Created by Father Sophrony at this time was a very large icon of Christ in Glory for a church in London (see first image). Writing to his sister he said ‘Not long ago, after a break of 36 years, I painted a big panel, 2 metres by 1 metre 30 cm.; it “turned out” better than I had assumed, even though technically I was dealing with materials completely unfamiliar to me.’31Ibid., p.124. To ameliorate the practice of icon painting at the monastery an icon studio was carefully built and this is where the icon painters worked, and still work today. As well as receiving training from Leonid Ouspensky in Paris, ‘Father Sophrony always tried out the artistic abilities of each new member and several hidden talents were discovered; these he nurtured and they blossomed.’32Ibid., p.126.

A number of the monastery’s main projects are described, including the decoration and liturgical layout for the 12th century church of All Saints (at the end of Rectory Road) which had formerly been the village’s parish church, although by then disused for many years and in a state of severe disrepair. Father Sophrony said that ‘I know that it was “condemned” to fall down and disappear. Now this church has become one of the most beautiful…’33Ibid., p.127. He said that this was the view expressed by people who were there on Holy Pascha (Easter) night. He also planned the gardens and every other aspect of the monastery’s construction and expansion. His ‘artistic nature showed itself in every detail of the building of his monastery…The outer shapes were conditioned by local regulations, but Father Sophrony made up for this by concentrating on the interiors.’34Ibid., p.127.

Other projects described include the design of the Stavropegic Cross in the mid. 1960’s,35Ibid., p.128. and the creation of the wall paintings for the refectory hall, which were started in 1977. All the main events from Christ’s life were painted and Father Sophrony ‘…would direct, correct and instruct at every step. He supervised all the colours, designs and layouts.’

The wall paintings in what would become the main church of the monastery dedicated to Saint Silouan the Athonite and next described. Here, Father Sophrony was able to draw on many years of profound reflection on the Divine Liturgy and its most suitable environment,

‘One can celebrate the Liturgy everywhere…, but IF one has the possibility why not celebrate it in a place which is as perfect as possible. The Liturgy is not like a piece of news that is in the newspapers, which is read and then thrown away by the evening – the Liturgy is an event in eternity.’36Ibid., p.132.

Writing to his sister he said that ‘Some years ago I was seized with the desire to construct a place of worship for the Divine Liturgy, and in my mind I built not one but dozens…In Europe, having lost the precious stillness of the desert, I had to devote myself in greater measure to the celebration of the Liturgy. This circumstance led to my wishing to find within my consciousness, and to bring into effect, a church, a “situation”, a space, for the Liturgy, such that even to a small degree it could express the spiritual essence of this Divine Act.’37Ibid., p.132, and ‘Letters To His Family’, Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 2015, letter 26, p.138. Father Sophrony was already 87 years old by that time and was keen to complete the work. Sister Gabriela lucidly explains the processes by which the chapel was decorated, the designs for the expressions of the faces, the colours used and many other fascinating details. ‘His iconographic designs were theologically conceived.’38‘Seeking Perfection’, p.12. and ‘He directed the drawing and the colours used, as well as their application. The main faces he painted himself, as well as some other parts according to his strength.’39Ibid., p.134. ‘…all the faces were painted by Father Sophrony himself. He would climb up the scaffolding and spend many hours in concentrated work.’40Ibid., p.136. The wall paintings were kept light and soft, whereas the iconostasis, which was deliberately low in height, was more strongly coloured. Again, much attention was given to achieve the ideal type of lighting for the special prayer of the monastery, shining ‘upwards from a hidden source onto the golden ceiling and then reflected down, giving a soft, warm and even light.’41Ibid., p.138.

In addition to this, Sister Gabriela also bestows ample information about the use of fabrics and textures (faktura) in the vestments, and their work in embroidery, gold and mosaics.

For me, the most fascinating part of the study was the subject of Father Sophrony as an iconographer. His approach to iconographic practice is described and this section is rich in quotations and comments of great interest. Sister Gabriela writes that by having ‘absorbed the iconographic tradition through observation and living with it, while leading a strict ascetical life…one’s understanding goes deeper, beyond the external aesthetic aspect.’42Ibid., p.154. ‘…he understood iconography in its essential form, as an inspiration for prayer, and a “springboard”, as he called it himself, to eternity. In this sense he was free from any attachment to any specific school or iconographic movement. His sole interest was to render the icon as authentically as possible.’43Ibid., p.155. As a result of this it is apparent that ‘One cannot classify his icons into any particular style or school. He took what he found best from each. His only concern was the icon itself, how best to express the given situation.’44Ibid., p.165.

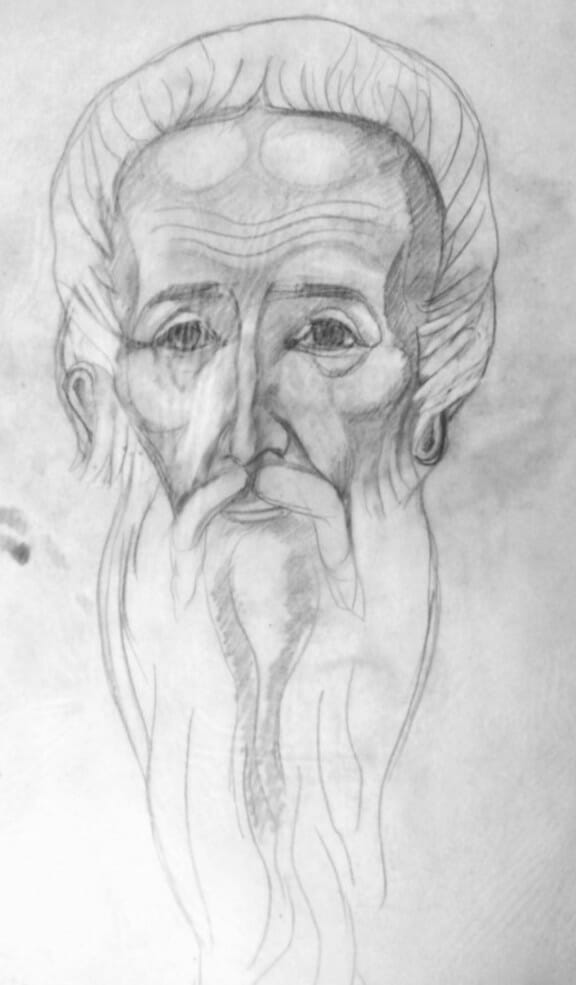

Father Sophrony’s approach was inherently minimalistic and ascetical, avoiding superfluous details. ‘Decoration for the sake of decoration was something he avoided…”To paint an icon is like writing a poem; one cannot add or take away a single word. In the same way the icon should only contain the necessary, not too little, not too much.”’45Ibid., p.164. His work was sober, ascetical and restrained, and he emphasised that nothing should impose itself, as ‘Even the faces should be discreet, so that one is free to look at them without being forced to do so.’46Ibid., p.171. He was not in favour of a copyist method and would often make many preparatory drawings (usually executed in pencil and sometimes also in pastels), especially for faces, giving every subject the deepest consideration and advising to,

‘Paint your icon as a poem, where every word is weighed and considered, in harmony. The icon shows what kind of person you are. There are many craftsmen, but few real iconographers. Make an icon, a beautiful icon, not like a worker, but like an artist.’47Ibid., p.169.

He also recognised that the work had to be specifically tailored to a location and its epoch, different to that which had been appropriate formerly and elsewhere, ‘In our days the strict Byzantine expressions did not correspond any longer to the present reality. He saw that a milder expression was needed.’48Ibid., p.155. The palette for the wall paintings in the chapel of St. Silouan were chosen ‘due to the English light, which is soft and diffused. Father Sophrony judged that it would be impossible to use strong colours, since these would look harsh and disturbing. On the other hand, in a country with strong light, like Greece, more dense and strong colours can be used without any problem…Each work of art is created for a specific place, at a specific time.’49Ibid., p.171.

Father Sophrony’s approach can be defined as one of profound thanksgiving, he wrote that ‘…now I cannot find ways to show God my gratitude for His “mighty hand” of the Holy Sculptor.’50Ibid., p.154, and ‘We Shall See Him’, p.33. ‘He had devoted all his capacities to the service of God and as such, when he started icon painting, he used the skills he already had…to express the icons, the faces and the striving towards the Eternal. The expressions in his icons stem from his understanding of ascetical and spiritual life acquired during his long years of prayer and repentance.’51Ibid., p.161. Sister Gabriela writes that ‘Father Sophrony…received abundant gifts and put them all at the service of God. He gave back everything he had received as an offering of thanks, in an all-encompassing wholeness. This all bore fruit in his painting. His position is unique in the sense that he passed through secular art, left it, denied it and gave it up to serve God. It was a total dedication and abandonment. Later in life he turned again to the tools he knew, which were brushes and paint, to express what he had learned and experienced during his many years of spiritual striving and ascetic work on the Holy Mountain. He did this not in any specific historical or secular style, but within the iconographic tradition. His works were fully and only meant as inspirations for prayer. He searched to express his acquired knowledge within the strict form of iconographical tradition. The long years virtually without painting are a crucial factor. It was a time of divestment before putting on a new garment.’52Ibid., p.160.

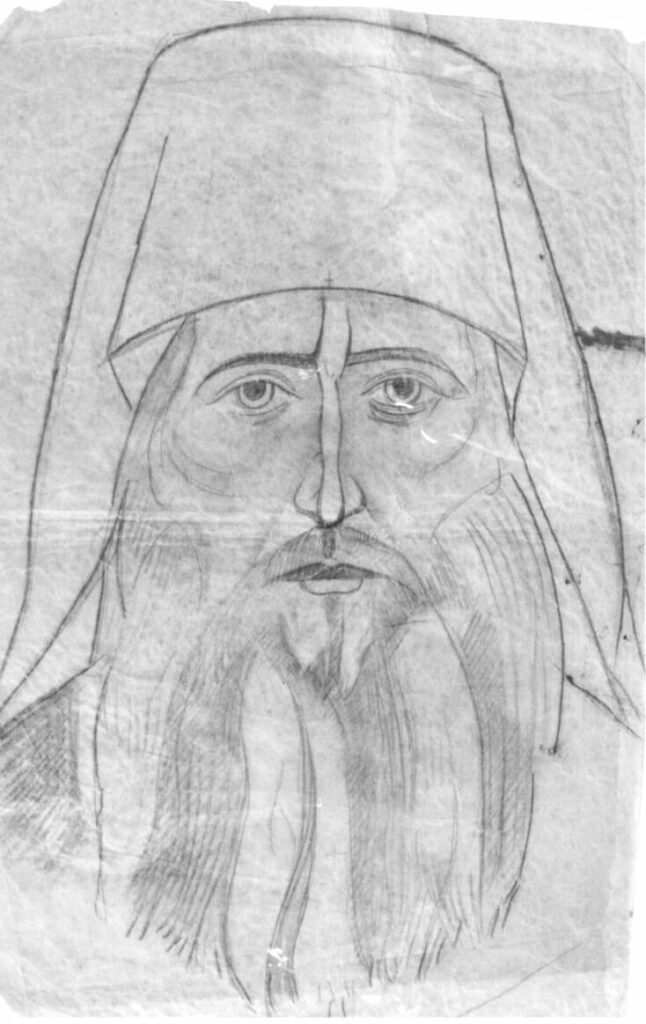

In the 1970’s Father Sophrony developed on Ouspensky’s icon of Staretz Silouan, ‘…adding two dark streaks in the beard, which were characteristic of the saint, and a vertical line on the forehead to the left of the bridge of the nose.’53Ibid., p.178. It is an especially precious contribution to the holy tradition that he created not only the written portrait of his staretz in the introduction to his book on the saint, but also in part the saint’s icon, in collaboration and over a period of several decades. In the chapel of Saint Silouan the saint is represented on the iconostasis, to the right of Christ, and at the centre of the west wall on the choir balcony (above the entrance door). The wall painting was made before the iconostasis panel icon, and this was the first occasion that Father Sophrony had painted his staretz in full face. The wall painting is part of a row of ascetics made before Saint Silouan’s canonisation and consequently his halo was added and inscription changed in 1988. The panel icon was made according to a stricter and more stylised form.

Ultimately however, no image was more important to Father Sophrony than the icon of Christ Himself. He said that,

‘We are looking for spiritual beauty when painting Christ, the Mother of God and the saints. Christ looked very ordinary, He could be in groups of people without being noticed. But His spiritual beauty was very great.’54Ibid., p.186.

The author tells us that ‘Special emphasis was always put on Christ’s humility. He should have a meek appearance, to show Him as the saviour of the world…Likewise, His gestures and whole appearance should be calm and peaceful. Christ’s image should be inspiring and comforting, especially in these troubled modern times. The strict, judgmental icons of earlier centuries are not suitable for our era.’55Ibid., p.186. In summation Sister Gabriela writes of Father Sophrony’s life that ‘This is the search for Christ, the yearning for close contact with Him and, within this, striving to portray His face in a correct and worthy manner, both in the inner life and in iconographic panting.’56Ibid., 188.

The following images are selected from the final section of the book (excluding appendices), which is a catalogue of twenty-eight of Father Sophrony’s drawings, primarily created between the mid 1960’s to the mid 1980’s, with two additional drawings made during his time on the Holy Mountain, spanning a period from 1921 to 1985.

This fascinating monograph represents a pioneering exposition and elucidation of the artistic and spiritual journey of Father Sophrony, and deepest gratitude is due to the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist and to Sister Gabriela for so generously sharing her many reflections and memories, and for the rich narration, documentation, original research and treasury of images of Father Sophrony’s iconographic work.

Footnotes

- 1Hereafter to be called Father Sophrony, reflecting Sister Gabriela’s preference throughout her books. At the initial publication of this article in January 2019 St Sophrony was not yet canonised.

- 2All published by the Stavropegic Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Essex.

- 3Cf. 1 Corinthians 4:15-16.

- 4‘Seeking Perfection’, op. cit., p.22, and Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), ‘We Shall See Him As He Is’, Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 1988, p.10.

- 5Ibid., p.23, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., pp.10-11.

- 6Ibid., p.25.

- 7Ibid., p.25.

- 8Ibid., p.58.

- 9Ibid., p.60.

- 10Ibid., p.63, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., pp.8-9.

- 11Ibid., p.64, and Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), ‘Wisdom from Mount Athos’, Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, 1974, pp.13-14.

- 12Ibid., p.64.

- 13Ibid. p.82.

- 14A term deriving from the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). Artists whose work continued his aesthetic, methods and ideas were said to participate in the Cézanèsque movement.

- 15Ibid., p.93.

- 16Ibid., p.90.

- 17Ibid. p.91, and ‘We shall see Him’, op. cit., p.15.

- 18Ibid., p.102.

- 19Ibid., p.108. Sister Gabriela indicates the existence of not only two but several icons attributed to the hand of Father Sophrony on Mount Athos. However, this question has been left aside in the book as research is still at an early stage.

- 20Ibid., p.106.

- 21This book ‘Staretz Silouan’ is now entitled ‘Saint Silouan the Athonite’ (Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 1991) and has been translated into twenty-five languages.

- 22‘Seeking Perfection’, op. cit., p.107.

- 23Ibid., p.112.

- 24Ibid., pp.112-13.

- 25Ibid., p.115.

- 26Ibid., p.115, and ‘Saint Silouan’, op. cit., p.274.

- 27Ibid., p.121.

- 28The Jesus Prayer or prayer of the heart.

- 29Ibid., from the foreword by Jean-Claude Polet, p.12.

- 30Ibid., p.123.

- 31Ibid., p.124.

- 32Ibid., p.126.

- 33Ibid., p.127. He said that this was the view expressed by people who were there on Holy Pascha (Easter) night.

- 34Ibid., p.127.

- 35Ibid., p.128.

- 36Ibid., p.132.

- 37Ibid., p.132, and ‘Letters To His Family’, Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, Essex, 2015, letter 26, p.138.

- 38‘Seeking Perfection’, p.12.

- 39Ibid., p.134.

- 40Ibid., p.136.

- 41Ibid., p.138.

- 42Ibid., p.154.

- 43Ibid., p.155.

- 44Ibid., p.165.

- 45Ibid., p.164.

- 46Ibid., p.171.

- 47Ibid., p.169.

- 48Ibid., p.155.

- 49Ibid., p.171.

- 50Ibid., p.154, and ‘We Shall See Him’, p.33.

- 51Ibid., p.161.

- 52Ibid., p.160.

- 53Ibid., p.178.

- 54Ibid., p.186.

- 55Ibid., p.186.

- 56Ibid., 188.